Lets start with the history. The earliest known linens were made from thin yarn spun from flax fibers to make linen cloth. Ancient Egypt, Babylon, and Phoenicia all cultivated flax crops. The earliest surviving fragments of linen cloth have been found in Egyptian tombs and date to 4000 B.C.E. Flax fibers have been found in cloth fragments in Europe that date to the Neolithic prehistoric age. Linen is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant, Linum usitatissimum. Linen ![5144083572_f581e99a3f_o[1]](http://www.magnificatmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/5144083572_f581e99a3f_o1.jpg) is grueling to manufacture, but the fiber is very absorbent and garments made of linen are valued for their exceptional coolness and freshness in hot weather. The word linen is of West Germanic origin and cognate to the Latin name for the flax plant, linum, and the earlier Greek, linón. Linen was sometimes used as currency in ancient Egypt . Egyptian mummies were wrapped in linen as a symbol of light and purity, and as a display of wealth. Some of these fabrics, woven from hand-spun yarns, were very fine for their day, but are coarse compared to modern linen. Linen fabric feels cool to the touch. It is smooth, making the finished fabric lint-free. It is a very durable, strong fabric, and one of the few that are stronger wet than dry. The fibers do not stretch, and are resistant to damage from abrasion. However, because linen fibers have a very low elasticity, the fabric eventually breaks if it is folded and ironed at the same place repeatedly over time. Linen is also mentioned in the Bible in Proverbs 31:22 says of a passage describing a noble wife, “She hath made for herself clothing of tapestry: fine linen, and purple is her covering.”

is grueling to manufacture, but the fiber is very absorbent and garments made of linen are valued for their exceptional coolness and freshness in hot weather. The word linen is of West Germanic origin and cognate to the Latin name for the flax plant, linum, and the earlier Greek, linón. Linen was sometimes used as currency in ancient Egypt . Egyptian mummies were wrapped in linen as a symbol of light and purity, and as a display of wealth. Some of these fabrics, woven from hand-spun yarns, were very fine for their day, but are coarse compared to modern linen. Linen fabric feels cool to the touch. It is smooth, making the finished fabric lint-free. It is a very durable, strong fabric, and one of the few that are stronger wet than dry. The fibers do not stretch, and are resistant to damage from abrasion. However, because linen fibers have a very low elasticity, the fabric eventually breaks if it is folded and ironed at the same place repeatedly over time. Linen is also mentioned in the Bible in Proverbs 31:22 says of a passage describing a noble wife, “She hath made for herself clothing of tapestry: fine linen, and purple is her covering.”

The Tabernacle during the Exodus, the wandering in the desert and the conquest of Canaan was a portable tent draped with colorful curtains called a “tent of meeting”. It had a rectangular, perimeter fence of fabric, poles and staked cords. This rectangle was always erected when the Israelite tribes would camp, oriented to the east. In the center of this ![tabernacle[1]](http://www.magnificatmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/tabernacle1.jpg) enclosure was a rectangular sanctuary draped with goat-hair curtains, with the roof made from rams’ skins.

enclosure was a rectangular sanctuary draped with goat-hair curtains, with the roof made from rams’ skins.

Inside, the enclosure was divided into two areas, the Holy Place and the Most Holy Place. These two areas were separated by a curtain or veil. It was the veil of the covering which was held up over the Ark by 4 gold pillars. This covering allowed for the ark to be held up by its two staves crossing over and being held by the “middle bar of the two sides 7 1/2 feet up into the smoke”. Inside the first area were three pieces of furniture: a six branched oil lampstand on the left (south), a table for twelve loaves of show bread on the right (north) and the Altar of Incense (west), straight ahead before the dividing curtain-veil.

Beyond this curtain was the cube-shaped inner room known as the “Holy of Holies” or Kodesh Hakodashim. This area housed the Ark of the Covenant (aron habrit), inside which were the two stone tablets brought down from Mount Sinai by Moses on which were written the Ten Commandments, a golden urn holding the manna, and Aaron’s rod which had budded and borne ripe almonds. Hebrews 9:2-5, Exodus 16:33-34, Numbers 17:1-11, Deuteronomy 10:1-5.

At the turn of the 20th century the Roman Catholic Church considered only linen or hemp to be acceptable as material for altar cloths, although in earlier centuries silk or cloth of gold or silver were used. At that time, the Roman Rite required the use of three altar ![original_altar_cloths-peter_anson-bw[1]](http://www.magnificatmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/original_altar_cloths-peter_anson-bw1.jpg) cloths, to which a cere cloth, not classified as an altar cloth, was generally added. This was a piece of heavy linen treated with wax or cera, from which “cere” is derived. It is the Latin word for “wax” to protect the altar linens from the dampness of a stone altar, and also to prevent the altar from being stained by any wine that may be spilled. It was exactly the same size as the mensa (the flat rectangular top of the altar). Above this were placed two linen cloths. Like the cere cloth, they were made of heavy linen exactly the same size as the mensa of the altar. They acted as a cushion and, with the cere cloth, prevented the altar from being dented by heavy vases or communion vessels placed on top. Instead of two cloths, a single long cloth folded so that each half covered the whole mensa was acceptable. The topmost cloth was the fair linen, a long white linen cloth laid over the two linen cloths. It had the same depth as the mensa of the altar, but was longer, generally hanging over the edges to within a few inches of the floor or, according to some authorities, it should hang 18 inches over the ends of the mensa. Five small crosses might be embroidered on the fair linen – one to fall at each corner of the mensa, and one in the middle of the front edge. These symbolised the five wounds of Jesus. The fair linen should be left on the altar at all times. When removed for replacement, it should be rolled, not folded. It symbolized the shroud in which Jesus was wrapped for burial.

cloths, to which a cere cloth, not classified as an altar cloth, was generally added. This was a piece of heavy linen treated with wax or cera, from which “cere” is derived. It is the Latin word for “wax” to protect the altar linens from the dampness of a stone altar, and also to prevent the altar from being stained by any wine that may be spilled. It was exactly the same size as the mensa (the flat rectangular top of the altar). Above this were placed two linen cloths. Like the cere cloth, they were made of heavy linen exactly the same size as the mensa of the altar. They acted as a cushion and, with the cere cloth, prevented the altar from being dented by heavy vases or communion vessels placed on top. Instead of two cloths, a single long cloth folded so that each half covered the whole mensa was acceptable. The topmost cloth was the fair linen, a long white linen cloth laid over the two linen cloths. It had the same depth as the mensa of the altar, but was longer, generally hanging over the edges to within a few inches of the floor or, according to some authorities, it should hang 18 inches over the ends of the mensa. Five small crosses might be embroidered on the fair linen – one to fall at each corner of the mensa, and one in the middle of the front edge. These symbolised the five wounds of Jesus. The fair linen should be left on the altar at all times. When removed for replacement, it should be rolled, not folded. It symbolized the shroud in which Jesus was wrapped for burial.

![poster[2]](http://www.magnificatmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/poster2.jpg)

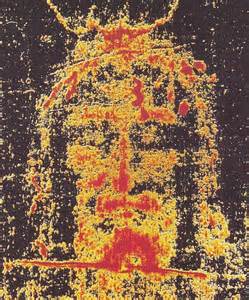

The Shroud is a linen cloth woven in a 3-over-1 herringbone pattern, and measures 14’3″ x 3’7″. These dimensions correlate with ancient measurements of 2 cubits x 8 cubits – consistent with loom technology of the period. The cloth is woven in a three-to-one herringbone twill composed of flax fibrils. The finer weave of 3-over-1 herringbone is consistent with the New Testament statement that the “sindon” (or shroud) was purchased by Joseph of Arimathea, who was a wealthy man.

In 1532, there was a fire in the church in Chambery, France, where the Shroud was being kept. Part of the metal storage case melted and fell on the cloth, leaving burns, and efforts to extinguish the fire left water stains. Yet the image of the man was hardly touched.

In 1534, nuns sewed patches over the fire-damaged areas and attached a full-size support cloth to the back of the Shroud. This became known as the “Holland” backing cloth. The Shroud was moved to Turin in 1578, where it remains to this day.

In 2002, a team of experts did restoration work, such as removing the patches from 1534 and replacing the backing cloth. One of the specialists was Swiss textile historian Mechthild Flury-Lemberg. She was surprised to find a peculiar stitching pattern in the ![OntstaanLijkwade_GiovanniBattista[1]](http://www.magnificatmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/OntstaanLijkwade_GiovanniBattista1.png) seam of one long side of the Shroud, where a three-inch wide strip of the same original fabric was sewn onto a larger segment.

seam of one long side of the Shroud, where a three-inch wide strip of the same original fabric was sewn onto a larger segment.

The stitching pattern, which she says was the work of a professional, is quite similar to the hem of a cloth found in the tombs of the Jewish fortress of Masada. The Masada cloth dates to between 40 BC and 73 AD. This kind of stitch has never been found in Medieval Europe.

The shroud is kept in the royal chapel of the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, northern Italy. In 1958 Pope Pius XII approved of the image in association with the devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus. Religious beliefs about the burial cloths of Jesus have existed for centuries. The Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke state that Jospeh of Aramathea wrapped the body of Jesus in a piece of linen cloth and placed it in a new tomb. The Gospel of John refers to strips of linen used by Joseph of Arimathea and states that Apostle Peter found multiple pieces of burial cloth after the tomb was found open, strips of linen cloth for the body and a separate cloth for the head. The origins of the shroud and its images are the subject of intense debate among theologians, historians and researchers.

New experiments date the Shroud of Turin to the 1st century AD. They comprise three tests; two chemical and one mechanical. The chemical tests were done with Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy, examining the relationship between age and a spectral property of ancient flax textiles. The mechanical test measured several micro-mechanical characteristics of flax fibers, such as tensile strength. The results were compared to similar tests on samples of cloth from between 3250 BC and 2000 AD whose dates are accurately known.

FTIR identifies chemical bonds in a molecule by producing an infrared absorption spectrum. The spectra produce a profile of the sample, a distinctive molecular fingerprint that can be used to identify its components.

Raman Spectroscopy uses the light scattered off of a sample as opposed to the light absorbed by a sample. It is a very sensitive method of identifying specific chemicals.

The tests on fibers from the Shroud of Turin produced the following dates: FTIR = 300 BC + 400 years; Raman spectroscopy = 200 BC + 500 years; and multi-parametric mechanical = 400 AD + 400 years. All the dates have a 95% certainty. The average of all three dates is 33 BC + 250 years (the collective uncertainty is less than the individual test uncertainties). The average date is compatible with the historic date of Jesus’ death on the cross in 30 AD, and is far older than the medieval dates obtained with the flawed Carbon-14 sample in 1988. The range of uncertainty for each test is high because the number of sample cloths used for comparison was low; 8 for FTIR, 11 for Raman, and 12 for the mechanical test. The scientists note that “future calibrations based on a greater number of samples and coupled with ad hoc cleaning procedures could significantly improve its accuracy, though it is not easy to find ancient samples adequate for the test.”

Most bloodstains on the Shroud are exudates from clotted wounds transferred to the cloth by contact with a wounded human body.

The blood on the Shroud is real, human male blood of the type AB (typed by Dr. Baima Ballone in Turin and confirmed in the U.S.). This blood type is rare (about 3% of the world population), with the frequency varying from one region to another. Blood chemist Dr. Alan Adler (University of Western Connecticut) and the late Dr. John Heller (New England Institute of Medicine) found a high concentration of the pigment bilirubin, consistent with someone dying under great stress or trauma and making the color more red than normal ancient blood. Drs. Victor and Nancy Tryon of the University of Texas Health Science Center found X & Y chromosomes representing male blood and “degraded DNA” (approximately 700 base pairs) “consistent with the supposition of ancient blood.”

The blood on the Shroud is real, human male blood of the type AB (typed by Dr. Baima Ballone in Turin and confirmed in the U.S.). This blood type is rare (about 3% of the world population), with the frequency varying from one region to another. Blood chemist Dr. Alan Adler (University of Western Connecticut) and the late Dr. John Heller (New England Institute of Medicine) found a high concentration of the pigment bilirubin, consistent with someone dying under great stress or trauma and making the color more red than normal ancient blood. Drs. Victor and Nancy Tryon of the University of Texas Health Science Center found X & Y chromosomes representing male blood and “degraded DNA” (approximately 700 base pairs) “consistent with the supposition of ancient blood.”

To learn more about Altar Linen listen to Learning about the Roman Liturgy today, January 14th, 2016, with Louis Tofari on Magnificat Radio at www.magnificatmedia.com at 10am, 1pm, 6:30pm, and 10pm, CST, USA. Click LISTEN LIVE. To purchase books and materials mentioned on Learning about the Roman Liturgy with Louis Tofari visit this link: Romanitas Press

Below is a neat video about Flax to Linen: