Every year the church goes through this; starting from the beginning of the Easter season of the liturgical year the Church has followed our Lord’s footsteps in the course of His apostolic ministry.

Throughout Passiontide, the Church, clad in mourning, contemplates the sorrowful events of the last year during Passion week and in Holy week, of His mortal life.

The hatred of the enemies of the Messias grows daily, soon it will be given full vent and Good Friday will remind us vividly of the most frightful of crimes, the drama of Calvary, ![veiled-cross-statues[1]](http://www.magnificatmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/veiled-cross-statues1.jpg) which was foretold by the prophets and by Christ Himself. Passiontide reminds us of Christ’s sufferings and is concerned more particularly with the last year of His public ministry, for it was then that the hatred of His enemies, increasing, daily, began to show itself more openly till it’s culminating point which the Church celebrates during Holy Week as she follows day by day in the footsteps of the Master.

which was foretold by the prophets and by Christ Himself. Passiontide reminds us of Christ’s sufferings and is concerned more particularly with the last year of His public ministry, for it was then that the hatred of His enemies, increasing, daily, began to show itself more openly till it’s culminating point which the Church celebrates during Holy Week as she follows day by day in the footsteps of the Master.

From the first Vespers of Passion Sunday, Holy Church, covers completely and with opaque purple veils, all the crucifixes, statues, and pictures of the saints, intended for worship and not for mere decoration. Some liturgical commentators have explained that this custom veiling is related to the Gospel account for Passion Sunday taken from the Gospel of St. John 8. 46 – 59. As Christ teaches in the Temple and declares He is the Son of God, Jews attempt to stone Him to death, so Jesus hides Himself as He leaves the Temple. In fact, Christ will not appear in Jerusalem again until His triumphant procession on Palm Sunday.

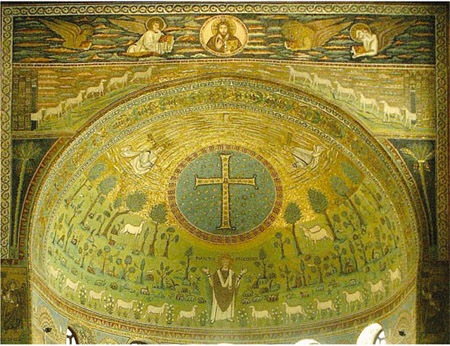

The Roman custom of veiling the High Altar cross stems from an ancient practice of covering the Crux Gemmata or jeweled cross. In Christianity, cross is a sign of victory, of life. We glory in the cross of Jesus; St. Paul’s Epistle to Galatians says, “But God forbid  that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ; by whom the world is crucified to me, and I to the world.” In the ancient Church the altar cross did not have a corpus. In fact, when the crucifix or corpus began to appear about the 5th century, it was considered scandalous by many. For many centuries altar crosses were made from precious materials; gold, silver, gilded wood, ivory, and often ornamented with precious stones. These crosses ornamented with precious stones were called Crux gemmata or gemmed cross. Several historical examples exist such as the Cross of Justin II from the 6th century.

that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ; by whom the world is crucified to me, and I to the world.” In the ancient Church the altar cross did not have a corpus. In fact, when the crucifix or corpus began to appear about the 5th century, it was considered scandalous by many. For many centuries altar crosses were made from precious materials; gold, silver, gilded wood, ivory, and often ornamented with precious stones. These crosses ornamented with precious stones were called Crux gemmata or gemmed cross. Several historical examples exist such as the Cross of Justin II from the 6th century.

The cross is veiled to indicate an attitude of sorrow for Christ’s forthcoming Passion but there is an even deeper liturgical meaning. All veils are a relic of the former custom of hanging a curtain between nave and sanctuary during the whole period of Lent. In earlier times, public penitents who were excluded from the church were not allowed to enter it until Maundy Thursday. When this practice was no longer in use, all Christians were to a certain extent considered as penitents and, although they were not excluded from the church, the sanctuary and all within it was hidden in order to show them that they were unworthy to take part in Eucharistic worship, and to receive their Easter communion until they had brought forth fruits worthy of penance.

On Maundy Thursday the Church strips her altars and silences the bells and organ. In this way the interior of God’s house, where many graces are bestowed on men and His worship performed with proper ceremony, gives an impression of mourning and the Church enables the faithful to share during this two week period of grief that she feels at the memory of the death of our Savior.

To learn more about Veiling of the Cross and Statues, listen to Learning about the Roman Liturgy today, February 18th, 2016, with Louis Tofari on Magnificat Radio at www.magnificatmedia.com at 10am, 1pm, 6:30pm, and 10pm, CST, USA. Click LISTEN LIVE button. To purchase books and materials mentioned on Learning about the Roman Liturgy with Louis Tofari visit this link: Romanitas Press